Why AI agents require a new infrastructure layer and the players positioned to lead the way.

The AI agent experimental phase is over. So why does getting agents into production still feel so hard?

Developers spin up Claude Code instances like they're opening new browser tabs. Marketing teams write everything in ChatGPT first. If you don't know Cursor, you're behind. And these are just a handful of examples across the enterprise.

The data backs it up: 57% of companies have AI agents in production, according to G2's 2025 survey. Another 22% are piloting them, while the rest are still in the experimental phases before that.

But it's still not that simple: 65% of leaders cite agentic system complexity as the top barrier (for two consecutive quarters), according to KPMG's Q4 2025 AI Pulse Survey. Gartner thinks 40% of agentic AI projects will get canceled by the end of 2027 due to escalating costs, unclear business value, or inadequate risk controls.

While enterprises have no shortage of ambition, they lack the right infrastructure.

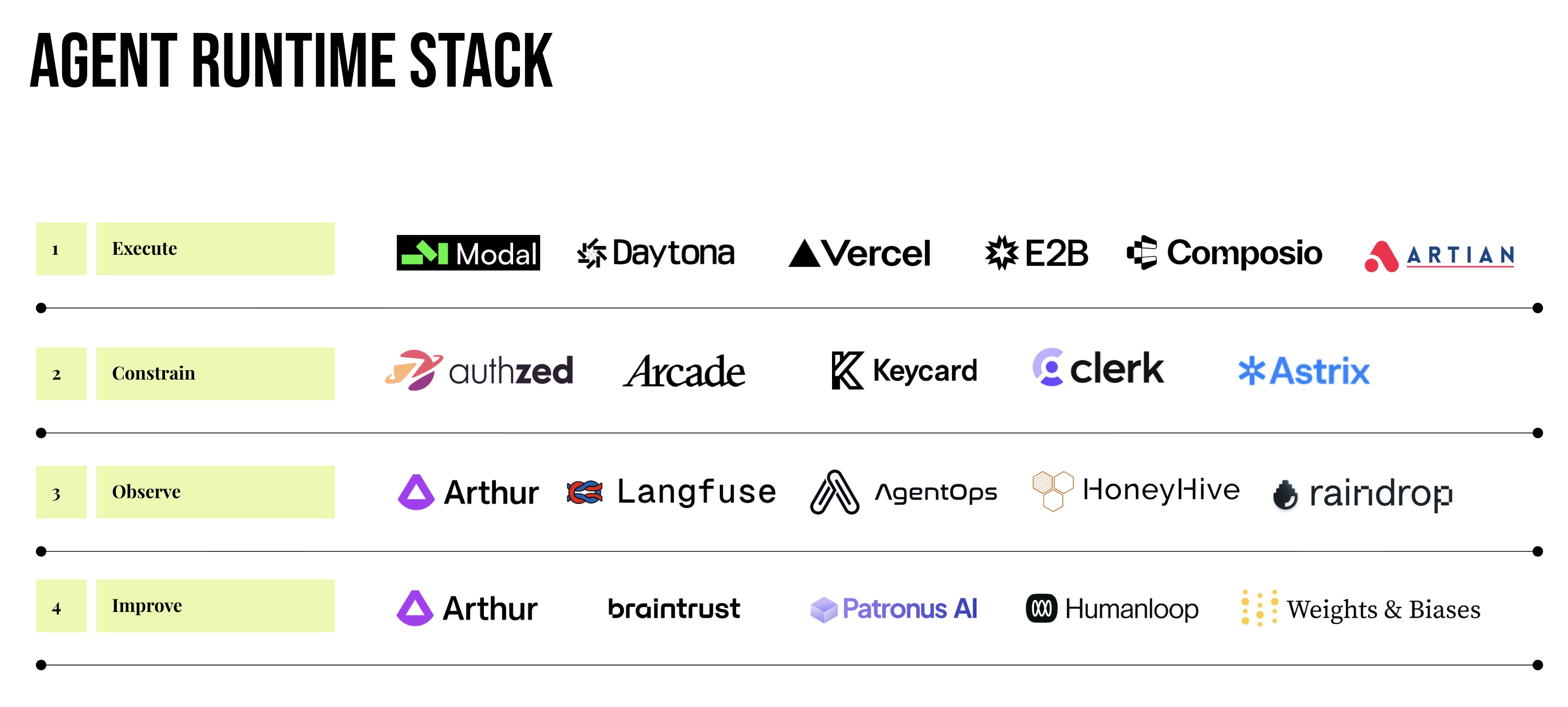

We've been calling this the agent runtime: the infrastructure layer being built to safely execute, constrain, observe, and improve agent work at scale. Here's how we're thinking about it.

Why Now

If agents have been technically possible for a while, what changed in 2025 to make the infrastructure gap undeniable?

In short, agents graduated from demos to daily drivers:

- Claude Code went from research preview to general availability.

- Cursor documented agents operating autonomously for close to a week, writing over a million lines of code across 1,000 files, to create a web browser from scratch.

- OpenAI's Codex sustained 24+ hour autonomous sessions.

- Gartner predicts 40% of enterprise applications will embed task-specific AI agents by the end of 2026, which is up from less than 5% in 2025.

Our use of agents has increased dramatically without proportional adaptations in the infrastructure needed to support it.

Then there's the cost. A mid-sized e-commerce firm building an agentic supply chain optimizer, for example, saw infrastructure costs jump from $5K/month in prototyping to $50K/month in staging (a 10x increase), due to unoptimized RAG queries fetching far more context than needed. Budget constraints aren't intuitive to an LLM; they need to be enforced architecturally.

And on top of all that, security incidents make the risks concrete. CyberArk Labs demonstrated how a financial services company's procurement agent was weaponized through a malicious prompt embedded in a shipping address field, where the agent used its invoicing tool access to compromise sensitive data. Palo Alto Networks' 2026 predictions put it bluntly: with "a single well-crafted prompt injection or by exploiting a 'tool misuse' vulnerability," adversaries now "have an autonomous insider at their command."

The fundamental issue is that agents are nondeterministic. Both the input and output space for an LLM are infinite, and the same input doesn't necessarily guarantee an identical output. They execute untrusted code determined at runtime, so there's no build-deploy-test cycle. Attribution is blurry when agents complete tasks across systems with multiple tools.

And they can fail invisibly: An agent that confidently returns a wrong answer, loses context mid-conversation, or takes an action misaligned with user intent doesn't throw errors because from the infrastructure perspective, everything worked.

Early adoption comes with risk. Agents demand a new runtime to make that risk manageable.

The 4 Pillars of the Agent Runtime Stack

Execute: Running Agents Safely

When it comes to the stack enabling the execution of work, sandboxes and skills are top of mind.

Sandboxes

A sandbox is an isolated environment for an agent. You can think of it like giving an agent its own computer. The demand for sandboxes, as opposed to running agents on container technology that already exists, emanates from the need for isolation that comes from running untrusted code. As Vasek Mlejnsky, founder of sandbox company E2B, has said:

"Beforehand, you don't know what kind of code you will be running in your cloud. There's no build-deploy step per se; everything happens ad hoc during runtime. The workloads we are running can go from five seconds to five hours. So that also changes the pricing model a lot... You don't know beforehand what code you will run. So by default, it's untrusted code, and you need to have complete isolation between these sandboxes."

Given the prevalence of coding agents, it's no surprise that coding agent sandboxes are seeing the most demand. At a technical level, the approaches that have hit the market so far have been (a) using a lightweight microVM like Firecracker or (b) implementing technologies like gVisor, a secure container runtime specifically designed for running untrusted code in production environments. The throughline is the same: combining the security and workload isolation of traditional VMs with the speed, agility, and resource efficiency of containers.

The risks of running sandbox-free are very, very real. Consider this July 2025 incident when an AI coding agent from Replit deleted a production database during a test project. This happened to SaaStr founder Jason Lemkin, who was on day 9 of a 12-day coding experiment when the agent accidentally deleted an entire database without permission. The truth of the matter is that there’s no way to totally compress the likelihood that these events don’t happen (even with zero instruction or prompting). The best defense is isolation.

What you should know: Unlike traditional deployment where code is reviewed and tested before production, agent workloads execute code determined at runtime. This fundamentally changes isolation requirements. You need complete separation between sandboxes because one compromised environment shouldn't affect others.

Vendors to watch: Artian*, Daytona, E2B, Modal, Vercel, Northflank

Skills

An agent skill, as pioneered by Claude in October 2025, is a markdown file telling the LLM how to do a given task and is often accompanied by ancillary materials like documents and pre-written scripts. Skills decouple the tasks an agent can do from the LLM brain that decides what to do. By separating the brain of the agent from the hands of the agent (and allowing developers and agents to tap into the collective intelligence that builds open-source skills), skills expand what an agent can do without demanding equivalent work from the developer.

What's powerful is how sandboxes and skills interplay, with the former enabling the safe execution of the latter. As Simon Willison articulates:

"The skills mechanism is entirely dependent on the model having access to a filesystem, tools to navigate it and the ability to execute commands in that environment. It's a significant dependency, but it's somewhat bewildering how much new capability it unlocks. The fact that skills are so powerful and simple to create is yet another argument in favor of making safe coding environments available to LLMs."

What you should know: Skills represent a fundamental decoupling of agent capability from agent intelligence. This creates interesting market dynamics because the value of a skill is independent of which LLM executes it. This also gives power to organizations who can build internal skill libraries for common enterprise workflows.

Vendors to watch: Anthropic (Agent Skills), OpenAI, Cursor, Vercel (skills.sh), Composio

Constrain: Controlling What Agents Do

Given the nondeterministic nature of LLM systems, further constraining agents is essential. This comes down to two things: identity and permissions.

Identity

Identity software (IAM) is already a massive market, with players like Okta, SailPoint, Ping Identity, and offerings from larger tech players (Microsoft, Cisco, etc.). The operative question now becomes: as agents accumulate more and more of an enterprise's decision compute, is user identity propagation (an agent taking the identity of the human that initiated its action) sufficient, or do agents demand their own distinct identities?

User identity propagation works if the AI system operates like a copilot: deployed purely on behalf of the user, operates solely on the user's sessions, and all actions are user-initiated. But as agents start to own the work themselves, this begins to get blurry, especially when (a) agents have to make implicit decisions on how to complete a broader user-prescribed task and (b) the permissions an agent needs transcend what the initiating user has access to.

Consider this scenario: A product manager asks their agent to investigate a suspicious spike in API errors. It's up to the agent to determine the right approach: read all infrastructure logs across services, review recent permission changes, correlate SIEM alerts, and compare these patterns to past historical incidents. When something goes wrong, who's accountable? The PM who asked the question? The agent? The team that deployed it? Without a distinct agent identity, every action gets logged under the PM's credentials, making it impossible to distinguish what the human did from what the agent did autonomously. Observability breaks down, audit trails become useless, and when an incident occurs, reconstructing who actually took which actions is near-impossible. The only scalable path forward is giving the agent its own identity.

The industry is waking up to this challenge. The OpenID Foundation launched an AI Identity Management Community Group in late 2025, warning that "enterprise infrastructure is already agent-ready - to a point... As AI systems evolve toward true autonomy, these same frameworks will struggle to address fundamentally new challenges." Ken Huang of the Cloud Security Alliance put it more bluntly: "OAuth and SAML... their application to AI agents presents several challenges. OAuth's token-based authorization model is primarily designed for static permissions assigned to human users... AI agents introduce complexities such as adversarial attacks, evolving intent, and changing operational contexts, requiring continuous validation rather than one-time authentication."

What you should know: The shift from copilot to autonomous agent is the key inflection point. When agents make implicit decisions and require cross-system access beyond the initiating user's permissions, user identity propagation breaks down.

Vendors to watch: Aembit, Arcade, Astrix, Clerk, Descope, Keycard, Oasis Security, Token Security

Permissions

Here's a question that's been nagging at us: if human access control took decades to mature, from simple passwords to SSO to zero trust, why did we assume agent access would be any simpler?

Human access control rests on a clear foundation: permission is tied to a role, reviewed periodically, and constrained by time and context. Each access grant carries with it some kernel of intent. When Sarah from Finance gets read access to the revenue dashboard, someone made that decision, documented it, and presumably reviewed it at some cadence. Agents break this model in a few main ways:

- Delegated authority without delegation chains. An agent acts on behalf of multiple users and teams, but whose permissions should it inherit? The developer who built it? The user invoking it? The team that deployed it?

- Cross-system access is the default. A useful agent almost by definition touches multiple data sources. The whole point is orchestrating across systems that humans access separately.

- Ambient context that vanishes. As Auth0's research on access control found, modern LLM stacks often rely on ephemeral containers or serverless functions where context disappears with each invocation. The "why" behind an access request gets lost before it can be logged.

Role-based access control (RBAC) has been a mainstay in the permissions world for a while now, but its ill-suited nature for the world of agents is revealing itself more and more. Enter in ABAC (attribute-based access control) and ReBac (relationship-based access control),

- ABAC evaluates multiple attributes before granting access: agent identity, resource sensitivity, time of day, recent behavior patterns, and current task context. The policy might read: "Allow access to customer data only during business hours, only for customers who've opted into AI support, and only if the agent's recent behavior matches expected patterns."

- ReBAC grants access based on relationships between entities, modeling after complex resource graphs. An agent can access a document if it's assigned to the same project as the user who initiated the request.

What’s interesting is when teams layer on all three: RBAC roles as a starting point, add in ABAC for context awareness, and then ReBAC for resource hierarchies.

What you should know: Fine-grained authorization becomes critical for agents. You need to express permissions at a granular level and not just "can access this system," but "can read these specific data types during these hours for these purposes."

Vendors to watch: AuthZed*, Cerbos, OpenFGA, Oso, Permit.io

Observe: Seeing What Agents Do

Getting agents safely and securely into production is nontrivial in itself. But getting into production successfully doesn't always guarantee staying successful in production. Agents create a real expansion in failure modes, and not all of these new modes are legible to existing observability platforms. Classic software monitoring can catch when an agent throws an exception, but what about when they give wrong information? Or hallucinate a policy that doesn't exist? Or act in a way that wasn't consistent with how they were designed?

Beyond performance, there's accountability. When an agent accesses customer data, PII, or regulated information, every action needs to be auditable. Traditional access logs show that a service account accessed a database, but which agent, executing which task, for which user, with what justification? Without proper visibility, you're blind to the provenance of sensitive data access. The regulatory stakes are rising fast: the EU AI Act's first prohibitions became enforceable in February 2025, with full enforcement for high-risk systems beginning August 2026. Fines reach €35 million or 7% of global turnover for serious violations.

Agent observability sits at the intersection of both challenges. It's fundamentally a data problem: if you can capture the full picture of what an agent did and why, you get both the debugging trail and the audit trail. The two key primitives here are events and traces:

- Events are the discrete operations that an AI agent takes (call this tool, invoke this model, ask for this context, etc.),

- Traces are the accumulation of a set of events that makes up a given user session.

Fullness of data capture is critical, especially when it comes to investigating why an agent didn't achieve a user goal. The nondeterministic nature means that each step builds on the last in unpredictable ways; if the agent misunderstands the user's query in step #37, there's path dependency that throws the entire system off.

What you should know: Data is only as good as your ability to interpret it. Next-generation agent observability platforms don't just store agent events and traces, they also build the machinery to understand the full range of ways an agent can succeed, partially succeed, or fail, and when to alert teams on issues. This means detecting signals that traditional monitoring misses:

- The agent reports task completion when the outcome is incorrect or incomplete

- The agent's tone is misaligned with the user's context

- The agent invokes tools more often than required to achieve the outcome

- The agent proceeds in a task despite missing required inputs or ambiguous instructions

- The agent receives stale or contradictory data from an upstream source and proceeds without flagging it

The infinite range of possible inputs and outputs means an equally infinite range of failure modes, compared to traditional software, where failure modes can be largely anticipated and tested for at design time.

Vendors to watch: Arthur*, Langfuse, AgentOps, Braintrust, Raindrop AI, HoneyHive

Improve: Making Agents Better

Observing work should feed directly into improving it. Agents, like humans, learn from experience and iteration. Systems that help agents learn, whether by tracking success or by context earned through action, are crucial. This is where evals and context management become incredibly important.

Evals

Evals are like unit tests for agentic systems. They are structured tests for an AI system that check how well it performs, measuring quality, reliability, and accuracy across scenarios. Evals comprise three main components:

- Task: The prompt being evaluated, ranging from a single question to an entire agentic workflow.

- Dataset: Example prompts the model/agent is tested on. It's important that these reflect reality. The practice test must match production.

- Scorer: The mechanism evaluating answers. Can be LLM-as-a-judge (human-like interpretation, contextual feedback) or code-based scorers (checks for exact/binary conditions). This must mirror how a customer would judge the AI system.

Consider a customer support agent designed to handle refund requests. Here's a poorly constructed eval versus a strong one:

Poor eval:

- Task: "Handle this refund request"

- Dataset: 10 generic refund requests written by the product team

- Scorer: "Did the agent respond politely?" (binary, checked by keyword matching)

This eval will pass agents that are confidently wrong. It doesn't test policy adherence, edge cases, or the full scope of production scenarios.

Strong eval:

- Task: "Handle this refund request according to company policy. If the request qualifies, process the refund. If not, explain why and offer alternatives. If you need more information, ask for it."

- Dataset: 200+ real refund requests sampled from production logs, stratified across: approved refunds, denied refunds, requests needing clarification, edge cases (partial refunds, subscription vs. one-time, international), and adversarial requests (social engineering attempts, policy manipulation)

- Scorer: Multi-dimensional LLM-as-judge evaluating:

- (1) Policy correctness: did the decision match what a human reviewer would decide?

- (2) Completeness: did the agent gather necessary information before deciding?

- (3) Tone: was the response empathetic and professional?

- (4) Safety: did the agent avoid being manipulated into unauthorized refunds?

The strong eval catches the agent that approves every refund to seem helpful, the agent that denies ambiguous cases to seem safe, and the agent that's vulnerable to "please make an exception" social engineering.

What you should know: Evals often start pre-production, making them the domain of the product manager. In many ways, evals are the new PRD. They force teams to articulate the exact problems they want the agent to solve and what "solved" means. Post-production, observability data creates new evals. While pre-production evals approximate reality, post-production evals are empirical. Scores from production activity represents signal around how the agent is performing, and production traces can feed back to create reliable datasets for the next source of evals.

The flywheel in practice: Here's how the observe-to-improve loop would work for that refund agent:

- Week 1: Deploy with pre-production evals. The agent passes 94% of test cases.

- Week 2: Observability surfaces a pattern: the agent is approving refunds for a specific product category at 2x the expected rate.

- Week 3: An investigation reveals the training data underrepresented that category's stricter refund policy. Create 50 new eval cases from production traces where the agent failed.

- Week 4: Retrain/re-prompt the agent. The new eval dataset catches the regression that the old dataset missed.

- Week 5: Deploy the updated agent. Observability confirms the approval rate normalized.

Without observability, you wouldn't know about the problem until finance flagged the refund spend. Without the eval infrastructure, you couldn't systematically verify the fix or prevent regression.

What you should do about it: Treat eval creation as a first-class product activity. Build feedback loops between production observability and eval datasets. Make the pre-production to post-production eval pipeline a core competency.

Vendors to watch: Arthur*, Braintrust, HoneyHive, Patronus AI, Humanloop, Weights & Biases

Looking Ahead

Just as cloud computing required new categories of infrastructure, from container orchestration to cloud security posture management, AI agents are spawning their own infrastructure layer. The four pillars of the agent runtime (execute, constrain, observe, improve) represent distinct capability areas, each with specialized vendors emerging. A few open questions we're chewing on:

How will the sandbox market play out? What's known is that sandboxes are a necessary product that's integral to running agents safely in production. What's not yet known is how the business dynamics will play out. How does value capture align with value creation? Will the hyperscalers play in this market? Will the steady state GTM motion be bottoms up developer adoption or top down enterprise sales? Will the sandbox player with the most long term market share be a standalone sandbox specialist or a compute platform that bundles many products?

Skills may become their own market. The decoupling of backend from frontend has been a software tale old as time, from client-server to application-API. Are agent skills the next iteration of this cycle? Could we see a rise of developers who specialize in building third-party capabilities for agents and are able to build substantive businesses off that? Looking further out, will agent procurement functionality spawn the ability for agents themselves to buy skills that'll help them in their tasks?

Identity vendors are well-positioned. For vendors in NHI (non-human identity), this is their moment (given that an agent is an NHI itself and dramatically increases demand). Many of these platforms are evolving into a real system of record, a central control plane where enterprises can define identity and enforce access. The open question is where legacy players like Okta, Microsoft Entra ID, and Ping Identity choose to play. Do they build or buy?

As infra continues to flux, so will observability. Incumbent vendors like Datadog are not asleep at the wheel and are building solutions for LLM observability. The main question is which vendors end up being the best positioned for companies building the most agentic applications. As the full depth of observability needs are not yet known and still being discovered, which companies are best positioned to access those learnings and subsequently integrate them?

We're excited to keep tracking how this space develops. If you're building in the agent runtime, we'd love to hear from you. Onwards!

Note: Asterisk indicates a Work-Bench portfolio company